by Katherine Ashe

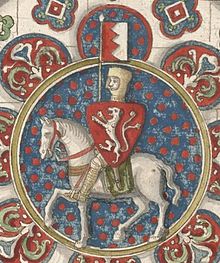

A grand feast was prepared for Twelfth Night, January sixth. The three soaring arches on each side of the hall were swagged with holly. At the Countess Eleanor’s whim, a swag was hung upon the great mural of the Montfort red lion rampant painted on the broad white wall behind the dais. The Montfort lion revelled in a collar of green holly leaves for Christmas. Simon raised his eyebrows at this liberty taken with his heraldry, but when the Countess offered to remove it, he let it remain. A large bough of mistletoe was found in Kenilworth’s woods and brought with high honor as an emblem of good fortune for the year to come. The hall’s floor was strewn with rushes from the Mere, with dried sweet woodruff, rose petals, costmary and verbena scattered liberally. “With all the villeins coming,” the countess’s Lady Mary remarked, “some good scents will be needed.”

Indeed the villeins were coming. The lord’s feast at Christmastide was the high point of every village calendar, but in its fullness it had been foregone at Kenilworth, due at first to debts, and then the lord’s absence. It was the countess’s thought that this old English ritual should be renewed.

Although the plenteous supply of beef, and all the beer that they could drink, was much anticipated, the villeins were in a stir to welcome their lord home with entertainments fitting to the day. They practiced their country dances, and those with drums or pipes made din of twitters and thuds long after vespers.

At Kenilworth’s bake shed in the inner courtyard, puddings steamed in iron cauldrons. Somewhere in those puddings’ lurked one hard bean that would crown some low person the king or queen for a day. Twelfth Night was Epiphany on the Christian calendar, the day of the arrival of the Wise Men at Bethlehem, but it was also the ancient feast of the Lord of Misrule.

It happily chanced that the Montforts’ return and rest, and readiness for entertainment coincided with Twelfth Night perfectly. Simon had never seen this English way of celebrating. His yuletides at Kenilworth, since he and the countess had received the manor as a wedding gift from King Henry, numbered only five, sober years mostly with young Prince Edward in residence and the Montfort finances strained. The villeins had their feasts of beef and beer from the steward’s hands, and nothing more occurred. It was with some uneasiness that the earl learned of the wild nature of the English festival in full cry.

Before dawn on the morning of January sixth, the squeal of slaughtered pigs and low of oxen at the knife filled the outer yard. Great fires were stoked and spits built to roast the beeves and hogs for the villeins’ feast. Pies of pheasant and partridge already lined the bake shed’s shelves. Beside them lay eels from the Mere, spiced, bedded in minced chestnuts and cased in pastry coffers. Tarts filled with custard and rose hip jam, or minced chicken and almond cream; and pommes dore: round gobbets of minced veal baked in a golden crust, stood ready to be served to the noble family. The finest tun of Bordeaux wine was hauled up from the tower’s pit that was the wine cellar. Trubody, the countess’ major d’omo who traveled where his lady went, had the tun set on a frame and fitted with a spigot. Sampling the wine, he found that it had not lost its savor, it was fully eight years in the barrel.

At the center of the hall a brazier was set, its fire blazing to drive off the winter chill. Early the villeins began to arrive: husbandmen in their wives’ kerchiefs and shifts, or with makeshift turbans and their faces smeared with soot as blackamoors. Wives in their husbands’ drawstring drawers, swaggering, a kitchen knife or poker stuck into a strip of leather serving as a belt. The village scapegrace came wrapped in a coarse brown robe tied at the waist with a piece of string. He rolled his eyes heavenward and clasped his hands in prayer in the pose of a friar. Twelfth Night was the holiday when all roles were reversed.

The villagers laughed raucously and pointed at each other’s transformations. Eventually they took their seats on long benches at the trestle tables set up along the walls of the hall. The table on the dais was extended, its mismatched boards and trestles masked by fine white linen drapery. Every chair that could be found was brought, for there were more dining at the high table this day than ever before. The villeins, early in their places, smiled shyly at Lady Mary as she checked her arrangements and was satisfied.

At noon the bell in Kenilworth’s tower was rung and the Montfort family assembled at the high table: the earl and countess at the center, with Peter de Montfort by the countess; then all the children, in precedence by age, were seated. Even young Amaury was there, come from Oxford in his black scholar’s robes. He rose and gave the solemn Latin prayer that let the feast begin. The Countess Eleanor took her husband’s hand as it rested on the tablecloth, and pressed it. He looked to her and smiled, his look warm with deep happiness and only the slightest tinge of restiveness about what this topsy-turvy festival of their folk was going to bring.

Seagrave, Steward-General for all of the Montfort estates, led the first course with the customary boar’s head wreathed in herbs. He presented it to Simon, slicing off the jowls and serving them to the countess and the earl. Then dainty dishes followed to the dais. Richard de Havering brought in a brace of geese with chestnut stuffing set round upon its silver platter with the pommes dore. Trubody held a platter of minced trout. Simon the cook and Ralph the baker came with the coffered eels and a blood pudding reeking with the pungent scent of thyme.

Henry Montfort carved for everyone at the high table. Young Simon poured the wine. The countess herself cut the trencher loaves.

Handy, Garbage and Slingaway, the kitchen boys, brought in great platters of beef for the villeins at the long tables, while the footman Gobehasty poured beer into the cups, pitchers and tankards that the villeins had brought with them.

When all the dishes at the high table were sampled, Havering gave a nod of special honor to the village reeve. The stout, flush-faced reeve stood up from the head of his table and with his horn blew a rough facsimile of a fanfare, signaling for the second course of feasting to be brought.

So it went, round after round through five courses until night came. Every villein was drunk and sated with more food than he or she ever had consumed before.

Young Eleanor collected the sops for the alms bowl. As quickly as she gathered them, her youngest brother, Richard, fed them to his little terrier underneath the tablecloth. At Eleanor’s protest, the countess’ almoner, John Scot, slapped the toddler’s chubby hand. Richard gave vent to a piercing scream, and went on crying till his brother Guy took him upon his lap and told him a tale of the Welsh war. Guy and his two elder brothers, eighteen, seventeen and sixteen years of age, already were men, living on their own as fighting soldiers. The younger children, brought up in Paris or traveling with their mother, hardly knew them. Richard stared at Guy in awe.

Far from the celebration fading into torpor as the feasting ended, it was now time for the high merriment of the Lord of Misrule. The puddings were brought out in which, somewhere, the magical bean lurked. Everyone but those at the high table had a slice.

It was Slingaway, the kitchen boy, whose tooth cracked the hard bean. He fetched it from his mouth with a triumphant grin. From somewhere came a crown of grass and reeds and it was set upon his head. The reeve ushered him up to the dais, to the earl’s side.

Simon, at ease now and merry from much wine, had no notion of what was happening. The Countess Eleanor whispered under her breath, “Slingaway has won your place, my lord. We must obey him as if he were you for the rest of the night.”

Slingaway posed with great hauteur by Simon’s chair.

Simon saw his lowest servant mimicking him rather well. He laughed and vacated his seat. Leaning with his back against the wall, his arms folded, a broad grin on his face, he watched with much amusement to see what the kitchen boy would do.

With a deep bow to the Countess Eleanor, Slingaway took his seat, his chest thrown out, his shoulders down, his neck stretched high as it would reach. He thrust his head back with a pensive frown, twisted his face into a squint, scratched himself and muttered loudly, “A pox upon hair shirts!” — bringing a roar of laughter from the long tables.

Young Simon snickered but his brothers looked uneasily to their father, fearing he would take offense. Simon was laughing heartily.

Now the Lord of Misrule stood. “Let there be dancing!” he announced.

From beneath the tables, where they had been stowed, assorted musical instruments were brought forth: pipes, drums and a home-made harp. The drums rattled out of rhythm, but everyone was far too drunk to care. Two pipers squeaked like manic birds. And then the music took on form, a fast, sprightly scattering of notes above a clear, swift drumbeat.

The Lord of Misrule rose from his throne again, turned and bowed to the Countess Eleanor. He bowed so low that his nose struck his knobby knee. But with a gesture admirable in grace, he held out his hand to her. She arose, curtsied to him, and taking his beer-scented hand, let him lead her to the center of the hall to begin the dances. The flaming brazier was carried to one side, and now the opened space was filled with village folk circling, bending, bouncing, laughing in gay time with the drums.

Young Eleanor grasped her young cousin Peter’s hand and led him to join in. The village reeve placed a holly wreath on Peter’s head, an ivy wreath on Eleanor’s, and the two led out the line of village children jumping, circling, joining hands and laughing till their sides hurt. Stumbling, jostling, shaken from his shyness, Peter led the dance faster and faster. Eleanor went whirling to her father, who was watching the merry mayhem with a broad grin. Her curling dark hair tangled in her ivy wreath, her eyes shining, her breath coming in gasps, she asked, “Have you picked a husband for me yet, Papah?”

“Not yet,” Simon said in mock solemnity.

“Then I won’t marry anyone but Peter!” She was off again, whirling flirtatiously with the boy she chose as her betrothed.

Tiring of her wild gigue with her kitchen boy, the countess came and joined her husband, by the wall.

As he watched their daughter, he took his wife’s hand again, his heart full of happiness. “She says she’s marrying Peter,” he laughed.

“She’s twelve. It’s time we thought of her betrothal,” Eleanor gently prodded.

“Perhaps,” he answered, gazing at the dance. He was not inclined to give it any thought just yet.

When the dancers, one by one, went back to the benches, their holiday energies spent, it was time for the village storyteller. He spun a tale of Hereward, then of Gamelyn and other ancient heroes of the English. He spoke in rhyming half-song till his hearers fell asleep.

It was full morning when the last of the villein revelers left Kenilworth’s hall. But the joy of the earl and countess’ homecoming lingered for weeks.