My father, Fredric Frank, a would-be screenwriter, was working then for the war effort as floor manager building the “Liberty Ships” that were to replace the Pacific fleet lost at Pearl Harbor.

He would tell stories of shipbuilding or his research for films. Stories, whether it was my father’s stories or my mother and grand aunt reading to me, have always been my fascination.

“It’s always best to begin at the beginning,” as Glenda the Good of Oz says. I was born in Hollywood in 1943.

From age 4 to7, when a child’s notion of the outside world is most likely to be formed, life was very Hollywood: dinners out every night at The Brown Derby or Sardi’s, and my father took me to the studio with him, or had my school bus drop me off at the Paramount gate where I joined the comedian Jerry Lewis barking at the iron kiosk filled with Dobermans. Our woofs turned the sleek black dogs into a fountain of leaping, shrieking, tooth-baring canine hysteria

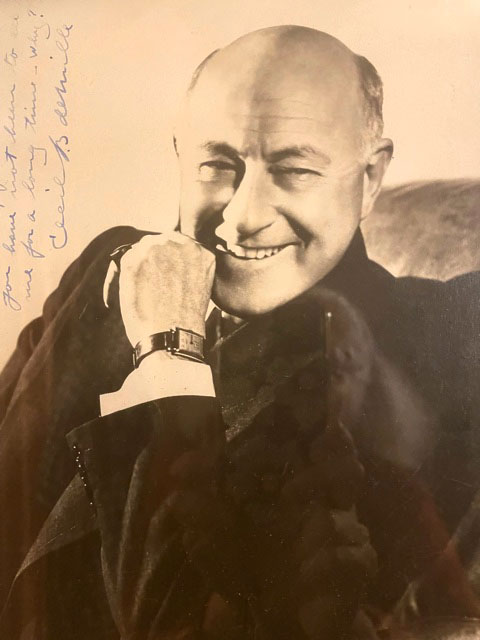

DeMille, my father’s boss, C.B. as he was called, was fond of me. I recall, at age four, sitting on his lap and his asking me what I thought of his film “Unconquered” which I’d just seen. I told him it was ridiculous. Shocked, he asked me why. “Well, when their canoe is going over the waterfall, Gary Cooper reaches out and grabs a tiny tree and hauls Claudette Colbert to safety. Nobody could think that little tree was strong enough.” Luckily for my father, it was a set problem not a flaw of the script. I was verbally adept at 4, and C.B. seemed a cozy stand-in for my grandfather.

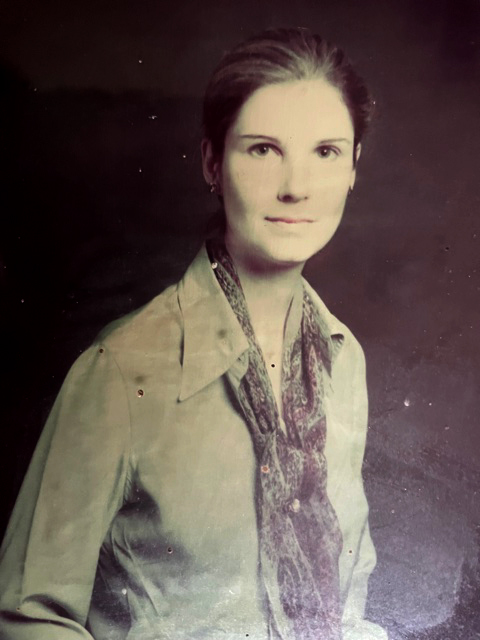

But my parents’ marriage did not last long. First, my beautiful, witty and well-read mother had a psychiatric breakdown shortly after my birth. I was sent to live with my father’s parents, Dan and Vera, for four years. It was a wholesome, stabilizing experience for when my parents reunited, I was returned to them and their marriage lasted only three more strained years.

In the wisdom of the California family court, I was allotted to my mother despite her history of alcoholism and violence. My father battled the courts for a year trying to get custody of me but failed. And by California law in the 1950s, I could not decide for myself where I wanted to live until I was 13.

In the next years my mother deteriorated markedly. It was not all bad with her, she read aloud to me, books that were far beyond my reading skills: Shakespeare, Churchill’s History of the English Speaking Peoples… Publicly she could be charming, whether it was with the Maharani of Baroda visiting Paramount or the taxi driver who gave up his day to chauffeur her. But between the alcohol and her physically violent temper, she deteriorated and it was dangerous to live with her. I managed to survive, fleeing to my grandparents by the time I was eleven. I was fortunate in having them to go to, and, in New Jersey, I was far beyond a court’s ability to send me back to my mother.

My life with my grandparents gave me perspective, and balance, to see my mother objectively even when I was very young, though I still take danger seriously.

Suburban life with my grandparents was steady and safe. Afternoons were spent in Aunt Ethel’s room where we munched our way through a pile of cream cheese and ginger marmalade sandwiches while Ethel read aloud and Vera sewed or knitted. It was very like their ownchildhood had been in the 1890’s. And Vera told stories of our ancestors’ lives in San Francisco.

In school I became interested in live theater which, after Hollywood, seemed like cottage industry. My first crush was on Nick De Noia, two years older than I and the founder of a large theater company composed entirely of children: Wizard Productions. I was assistant producer. We staged “The Wizard of Oz” with 40 little Munchkin children and a teenage cast of 20 in the 4,000-seat Park Theater in Union City, New Jersey. I played Glenda.

While my fascination with Nicky, a martinet of a director, faded, my theater interest lingered long enough for me to study at Temple University and Pasadena Playhouse. My father got me a job as intern at The Players Ring, Hollywood, where we had a parade of movie stars hungry for even a slim chance to practice their art. When my father was in Madrid writing “El Cid” for the Bronston film company, I went over to spend the summer with him. They were simultaneously shooting “King of Kings” with the famed Irish actress Siobhan McKenna as Mary. When Siobhan confided in me that, as an actor, one spends one’s life praying for a role, then convincing oneself that the role is worthwhile, I finally dropped my interest in theater.

From early childhood my marked talent was for drawing and painting. Every Christmas and birthday I was given one of the massive Skira art books on classical European art. I vividly remember, when I was five, my parents’ summoning me to a conference. I recall sitting on the couch, my feet dangling, as I waited for what serious thing this was all about. The issue was, would I like a professional water color or oil painting set? I asked what oil paints were. My father explained they came in tubes like toothpaste. I replied, no, I’d get it in my hair. They got me the oil paints, canvas board and a small aluminum easel. This set had the fate of most new toys, I did two paintings and forgot about oil painting until I was twelve.

At twelve, in New Jersey, before I became entranced with Nicky and Wizard Productions, I took still life and portrait painting lessons with Harriet and David Boyd. At 19, on Siobhan’s advice, I returned to painting. I was in college at NYU, but still taking singing lessons. On November 2, 1962, Election Day, there were no classes. So I took my first little painting to an art shop I passed on my way to my lesson. (I’m very nearsighted and have shaky hands but my chosen métier was a meticulous surrealism that I painted with my hand braced on a dry spot on the canvas and my nose about five inches from the wet paint .) The woman in the art shop looked at my little canvas and, in a rich New York accent, said “Take som moah aht lessons, then may Oi can help yuh.”

Thoroughly insulted, I took back my painting, went over to Madison Avenue and went from gallery to gallery. By the end of the day I had two galleries representing me. (I had no idea you were supposed to have only one!) They were the Dorsky Gallery and the Braverman Gallery. I started painting in every spare moment, while still doing some college theater (Electra in “The Flies”). Not surprisingly, my health broke down. I left NYU at the beginning of my fourth semester. Home again in New Jersey, I turned full time to painting.

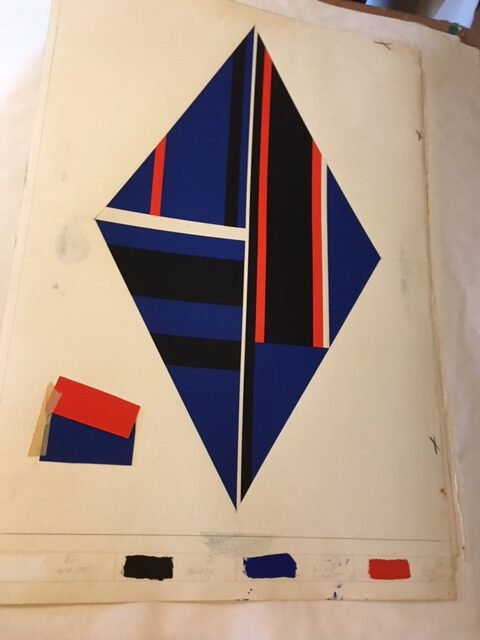

1963, Oil painting on Masonite, 4′ X 5′, by Katherine Ashe (nee Ann Frank)

In the collection of Wyoming Seminary, Wilkesbarre, PA. The title is a quote from Goethe, “Faust”.

When both the Dorsky and Braverman galleries closed, I sought new representation. I was doing so well that I tried an especially prestigious Madison Avenue gallery. But the owner took me by the hand to his back office and showed me a black leather “sensory deprivation mask” used in sadomasochistic practices. Smiling, he said he’d show my work if I’d join in his “games.” I fled.

The following week I was invited to dinner by a major New York art critic. (Let it not be said that men don’t make passes at girls who wear glasses, and I was pretty.) My “date” let me know that, for certain (sexual) considerations, he would promote my art work.

I stopped painting. Years later I founded the fine arts print publishing company, Contemporary Artists, Inc. so that young artists could make a living without facing sexual demands.

At age 21 I had already ended two careers. I was back in college, at The New School which required that the first two years of college be in credits transferred from some other school. This was the mid-1960s and New York City was a smorgasbord of higher education. My chief academic interest was philosophy. I took classes at Columbia, City University and Hunter College with such luminaries as Hannah Arendt. My home base, the New School, brought me Dr. Henry Pachter with classes on The Philosophy of History and The History of Revolution. Dr. Pachter and I became friends to the end of his life; he was a major guide and influence in my writing Montfort.

My class requirement at The New School I met with an art form utterly remote: Chinese art. My teacher, Dr. Chu Chai, told us of Rudi’s Oriental Art shop on Seventh Avenue. There I found a large vase, black with boughs of white plum blossoms on its four sides I bought it with my total savings: $250. Carrying it home, I met Dr. Chai. Unpacking the vase from its two grocery bags, I set it on the sidewalk. “Imperial piece,” Dr. Chai gasped.

Now I had a new career. I imagined I’d find numerous great works of Chinese ceramics! To that end, I began compiling a directory of Chinese ceramics, from archeological to present day reproductions. I organized each category by the chemistry of the body materials and glazes so, knowing nothing but what I saw of a piece, I could look it up. A teacher at The New School was editor-in-chief at Funk and Wagnalls, the dictionary publishers, and the company was pursuing a new policy of publishing trade books. He commissioned me to enlarge my little directory into The Dictionary of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, with an advance that enabled me to travel.

Now I developed my research skills, wading through every book I could find on Chinese ceramics in the New York Public Libraries and studying the collection at the Metropolitan Museum. At first I was permitted to use only the museum’s public card catalogue. But, from old books, I knew of much more that the museum held. How to get at it? Going up the main staircase, where the names of major contributors to the museum were carved into the marble, I noticed a Chinese art dealing couple I knew well. I complained to them. The next day I had a call from the Oriental Art Department offering me their services. Not only was their full card catalogue available, but I could summon up pieces from “the tunnel,” the emptied, vast water conduit that runs under Fifth Avenue, where the museum stores its works that won’t be damaged by dampness.

The department secretary contacted me when Walker Publishing asked her for the name of someone who could write a book on Chinese Blue and White ceramics for their art book series. That project branched into others: ghost writing a book on the Imperial Palace Museum and working for Christies auction house, newly moved to New York. (By this time I was about 25.)

The Christies job provided photos for my ever-expanding Dictionary. I now had experience in research both in the US and abroad. Much of my work on the Dictionary entailed study at the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and The Percival David Foundation. My massive tome staggered on until Funk and Wagnalls was bought by the L.A. Times and all the trade books were cancelled.

So end my third career. The obvious alternative publishers had series of books on Chinese ceramics that a single resource might make superfluous. The final blow came when Abrams sent my immense manuscript to an authority on Chinese ceramics who wrote back that the book was totally disorganized. The book was not arranged chronologically!

China was essentially closed off from the West. But I had a contact there, Rewi Alley, a New Zealander who fought there in World War II, founded a Chinese orphanage as a model commune and was an amateur ceramics archeologist. Believing in peace through trade, I’d been reading about China’s five-year development plans. Where they were falling behind markedly was in beef production. So, with Rewi’s connections, I went into a new business. I’d supply quick-frozen bull sperm to the Inner Mongolian Grasslands Institute.

It was fun at parties when asked what I did. But it was not as crazy as it sounds. Agway had a new computerized system to find the exact bull whose sperm was right for a certain rangeland’s needs. The sperm, in glass ampules, fit tidily into a cryogenic shipping canister. It could be flown, by Aeroflot, to Ulan Bator, picked up by duster-clad, jeep-driving ladies of the Institute and put to work in improving the livestock in frigid Mongolia with genes from North Dakota.

Alas, someone in China’s bureaucracy thought it peculiar that bull sperm should be coming via a young lady in New York. The Institute switched to the more appropriate seeming Texas Cattlemen’s Association and got Santa Gertrudis sperm, suitable for Texas’s hot summers.

I was at a loss what to do next. I thought again about my deterring experience with the Madison Avenue galleries, and I founded Contemporary Artists, Inc. Limited edition fine art prints were enjoying a booming market, and could provide a means for young artists to be free of coercion.

I published fourteen limited editions with major and up-coming artists . It was immensely enjoyable working with the artists, matching them up with just the right printer. My guide in all this was Paul Cummings. Paul and I had been dating since my days at the Dorsky Gallery. Paul was a rather mysterious eminence gris in the art world. Author of The Dictionary of Contemporary American Artists, a book every serious gallery of modern art used to select whom they represented, he had a strong hand in what was shown. He also was advisor to the prestigious Whitney Museum. While he encouraged my painting, he worried about me and, when I quit, it was he who bought me books on Chinese ceramics. Needless to say, I’d not have attempted Contemporary Artists without his guidance. But even Paul could not sustain the vitality of the print market, which crashed in 1977, bringing to an end Contemporary Artists’ viability.

So there went yet another career in my still young life. While one may look on this as exceptionally bad luck, I look on it as affording me the opportunity to do different things, instead of being locked into one set of interests. Life can be astonishingly rich.

But at this point I took a break. The end of Contemporary Artists was traumatic. I turned to soothing myself by writing fiction for a time. While engaged in this happy, solitary occupation I came to a need for a bit of research. What was going on in England in 1258? I hauled out my Britannica and discovered the Barons War, led by Simon de Montfort.

Despite Dr. Pachter’s class on the history of revolution, this was all new to me. I looked up Simon de Montfort. Inexplicably, I felt the Britannica’s article was doing him severe injustice. I had no reason to criticize the Britannica, just a profound gut feeling. A week later I was attending the reopening of the Ottendorfer Library, around the corner from my New York apartment. The Ottendorfer was set up to have its stacks in a herringbone configuration, the end of each row visible down the center aisle. As I stood at the back sipping lurid punch, my very nearsighted eyes fixated on a distant set of green bindings. I went to the row, pulled one of the green bound books off the shelf and let it fall open at random. It opened to a description of Montfort’s death at the Battle of Evesham. Its words were in high in praise of Simon de Montfort — the founder of modern democracy! I shut the book, determined that the next thing I’d do would be to devote myself to researching this virtually unknown, pivotal person in our history. The year was 1977.

That commitment developed into research, writing, more research and rewriting that spanned 35 years. The first eight years I spent focused on writing the first draft. I did my research at the British Library, the Bibliotheque Nationale and my home base, the New York Society Library, a private library founded in the reign of King George IV and accumulating books ever since. Members (which I was) were free to roam the several floors of stacks. While abroad, I traveled to most of the places significant in Montfort’s history.

Initially I had done the usual thing. With a couple of chapters and an outline, I went to the son of the agent I’d had since my Chinese ceramics days. In a week he was back with a contract from Playboy Press. I explained it wasn’t that kind of book, and I wouldn’t touch Playboy with a barge pole. He protested that they paid the most and published some non-salacious works. Nonetheless, I replied that I’d complete the book before offering it again.

And so I did. It was 1985 when I final emerged with a 1,500-page first draft. Now I faced a sea change in the publishing of historical novels. Heroic white males were forbidden, unless the book was a mystery or war book. Montfort would have to be changed to a book about a woman. My advisor at that time, Dr. Madeleine Cosman, founder of The Institute for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at the City University of New York, practically choked with laughter, “We’ll just call him ‘Simone de Montfort’!”

I can appreciate the impulse to try to level the history of accomplishment from its white male dominance by publishing works about women, but my intent was to explore who Simon actually was and how his creation of England’s Parliament happened. I wanted my book to come as close to informed speculation as research could accomplish, yet with a sense of how things could have happened in life as lived. A novelized biography was what I was writing. There is an abundance of 13th century material, even including eye-witness accounts in the Chronica Majora and other contemporary works, detailed down to the weather reports and with some actual quotations. I had no intention of abandoning my search for truth for the sake of a contract and the impressive colophon of a major publisher.

By 2008 I’d had various agents, but editors were still set against white male heroes. I turned to self-publishing. The company I chose, BookSurge, was being bought by Amazon, merging into the not-yet-major CreateSpace. I’d divided my still 1,500+ pages into four volumes and published the first volume, Montfort, The Early Years.

Between 2008 and 2012, when the last volume was published, I went on with my research, finding more documents, refining my perceptions of why the known events took place and what their consequences were. Though I did other things, my constant reading was books on 13th century life, from finance and banking to cookery, agriculture, customs, religion, trades, law, combat… and I read the books that Simon read, lent by his Franciscan friends and mentioned in their covering letters in the Monumenta Franciscana. The breadth of my studies sharpened and shifted my understanding of the significance and consequences of historical events.

My first volume came out with a tempting blurb, supported by Dr. Cosman, proposing that Montfort was the father of King Edward I. The book provides a great deal of evidence from 13th-century documents, countering King Henry III’s assertion that Edward was a miraculous conception achieved by Saint Edward the Confessor. (Henry III and his queen, Eleanor of Province, had a history of infertility.) Crucially, there is the eye witness account of the Churching of the Queen, at which Henry appears to have learned of a more normal mode of conception. He turns violently on his best friend, Simon, with a series of veiled and absurd accusations; he dared not expose the illegitimacy of his much needed heir. Montfort was forced to flee at once into exile.

Other writers pass off this significant event by saying King Henry went mad. But knowing that the Churching ritual required the Queen to make a full life confession to the Archbishop throws a very different light on the event. Also royal letters show the royal couple were at Kenilworth, Simon’s castle, on September 15, nine months before Edward’s birth.

Horrifically, my well-researched proposal that Simon was the father of Edward brought on a deluge of author bullying. Seizure of my Amazon sale page, rape and death threats on Goodreads, a hacking of my computer so that all my passwords were changed and, even when I tried recently to enter an edit of Book I, the file in my computer was corrupted in a way that no purely mechanical glitch could have done.

At the peak of the attack, in 2014, an organization called Stop the Goodreads Bullies came to my aid and that of another author suffering the same sort of onslaught. Responding to STGB, Amazon changed the algorithm of their sale pages so they could not easily be gamed. And they bought Goodreads, removing the attack messages and blocking the attackers. Montfort, The Early Years eventually achieved Amazon’s Historical Novel Best Seller List for 30 consecutive weeks.

We live in a difficult time when the ability to be vicious anonymously appeals to thousands who, with a touch of a few buttons, can imperil a stranger’s life. I’d suffered a “panic attack” so severe that a hospital nurse nearly had to cut open my trachea for me to breathe. Could anyone have imagined that a technology that brought the laudable goal of people everywhere being able to communicate with each other might unleash such cruelty.

Let us leave that subject. During the many years I was working on Montfort, I did do other things.

In 1980 I got married. I’d known Peter Wynne since I was in a high school production of “The Boyfriend” (1961.) I got him involved Nicky’s Wizard Productions and we dated after I left the company. Unfortunately for Peter, he introduced me to a poet whom I imagined I could help. Alex, a friend of “the Merry Pranksters”, was one of the first to manufacture LSD. I didn’t try the stuff and tried to persuade him that the poetry he wrote under its influence wasn’t very good. That relationship didn’t last long.

In 1978 I encountered Peter Wynne in New York. He was now a journalist and soon to be a New York theater and opera critic, going to eight openings a week. Occasionally I went with him, emerging from my concentration on the 13th century. In 1979, before we were married, we bought a house in rural Pennsylvania and I moved there, with books kindly sent to me by The New York Society Library. We’re still there. As I write, the rain storm we’re having (8:25 PM, October 26, 2021) is giving me a view of our waterfall white and overflowing with threat of flood down below our mountain.

By 1987 I was curious if I could tell a story in less than 1,500 pages. My first attempt met the waste basket. The second was suggested by the manager of American Stage Company who knew I wrote on historical subjects and probably imagined I was experienced in play writing. It was to be a play on Columbus for 1992, to be performed out-of-doors on a Staten Island beach park overlooking Manhattan’s skyscrapers and the Statue of Liberty. The commission was also taken up by The East Lynne Company to tour cities named after Columbus. I wrote a pageant play, but the protests of Native Americans against Columbus scotched any productions. Ironic since I’m partly Mohawk.

Okay, I’d write about Indians. There followed “Vriesland,” on the Dutch massacre of the Lenape Indians at Hoboken (New Jersey) in 1644. Then came “The Medicine Man,” about my Mohawk grandmother and her father who taught her herbal medicines. She became quite rich selling herbal cures in Boston by the 1920s.

After that I expanded my focus to some short plays: “Burton in Africa” and “Supper with the Pope,” on the Borgias, produced by a Lower East Side company that did brilliant productions under the name Shakespeare in the Parking Lot. For a contest, I dashed off a 20 minute piece called “Martha Speaks Up,” on Martha Washington, only to have the contest limit entries to five minutes.

In 1990 Peter left journalism to teach at the State University of New York at Binghamton. We were now both full-time residents in the country. But when, three semesters later, New York cut its funding to its state universities, Peter was out of a job.

At a chamber music concert we met a crew from a new public radio station, WJFF-FM in Jeffersonville, New York. They roped us in to volunteering. I learned radio technology, which was even further from my expectations than selling bull sperm to China. Peter had a Sunday opera interview broadcast, and I was the station’s engineer from 5:00 P.M. to midnight. The owners of the station went off to Alaska, so we learned “on the job.” There was a scattering of “dead air,” yards of tape went on the floor, and one broadcast, of jazz pianist Marian McPartland, was broadcast with the tape inside out until I got something else on and rewound the tape right side up.

There was a program aired late on Sunday nights which seemed to me to be thoroughly obscene. By this time the owners were back and I complained. The wife mused, “But we get fan mail for it. Come to think of it, the letters all come from a prison.” I asked if the writers were paid up in membership. They weren’t. But she wanted some kind of drama program to fill the spot. I told her I wrote plays and would be happy to adapt them to radio. Thus Jefferson Radio Theater was born.

In a nearby town there was a small theater company called The Little Victory Players Theater, and several actors from the TV show “As the World Turns” had country houses in the vicinity. I assembled a professional cast of 15. I reveled in writing historical plays for radio! Unlike with film, one could have as many characters as one wished with actors doubling in roles, and however many “settings” you wanted. All was at practically no cost except for the actors, music and sound effects.

My Jefferson Radio Theater was funded by The New York State Council for the Arts, The Pennsylvania Council for the Arts and The New Jersey Council on the Humanities. “A Life or Love” was an early candidate, from a play about my grandmother’s sister Mabel who eloped with the son of the first president of Cuba in 1903. Then there were new plays, “Being Murietta,” about the Californios during the Gold Rush, and “The Richest Woman in the Western World” on Eliza Jumel who rose from a life on the streets of Providence, Rhode Island, to corner the New York City real estate market and nearly rescue Napoleon after Waterloo. (All true.)

When Peter moved from volunteer WJFF-FM to professional WVIA-FM in Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, I went too and produced “Vriesland.” Peter did two weekly shows. One was interviews with the personnel of operas opening at the Met or New York City Opera. It dealt with the whole span of theater arts, from singers to designers, stage directors and the Met’s astounding technology. The other was a similar set of interviews about Broadway and Off-Broadway shows. As a well-respected critic, Peter had access to top people. And I was his sound engineer. With multiple mics for group interviews, a small digital tape recorder, a Mackie board to control each mic and, what seemed, to one interviewee, “a mare’s net of wires,” I was having a grand time.

I recall one interview with writers Betty Comden and Adolph Green (perhaps best known for the Leonard Bernstein musical s “On the Town ” and the movie “Singin’ in the Rain”.) I’d broken my leg, so we arrived at Comden’s apartment with me in a wheelchair, our equipment piled up on a board across the arms of the chair for my mobile studio.

But live theater was still in my future. At an event for the debut of a new theater company in New York, the project of a friend, the actress Celeste Holm arrived, announcing “I have the flu!” (Celeste, an Oscar winner, according to some wag “would attend the opening of an envelope.”) With her cheery announcement, everyone crowded to the far end of the room, except me. I sat down beside her and said, “I’ve had my flu shot!”

It had occurred to me that Celeste would be perfect for the “Martha Speaks Up” monologue. And she was. She arranged for a reading of the little play at the Armory in Central Park, with various television series producers invited with the aim that they star her in a series to be called “The Washingtons.” A “deep-period” piece is a costly thing to produce, but a producer from PBS went for it.

The project was to be a 13-hour series that I was to write, with Celeste as Martha. I started to work on the scripts, doing my usual in-depth research and staying with friends in Virginia for a part of each of three years.

In the meantime, Celeste was hired to do a television series called “Promised Land.” The first day of shooting, in mountains in Utah, this actress far into her seventies was required to dance with a group of children in 100+ degree weather. The result for Celeste was congestive heart failure. She courageously struggled through her contract, but was in no condition afterward to take on “The Washingtons.”

But another opportunity had opened for me at the Armory event. The head of the Parks Department came to me to say the department had several historic houses. Would it be possible for me to write a play for each, to attract more attendance at the sites. Oh, yes. I could do that.

The result was a one-man show, “An Evening with Edgar Allan Poe.” In the event, it turned out that while the Parks Department owned and maintained the Poe Cottage in the Bronx, the Bronx Historical Society controlled the interior, and they were aghast at the prospect of twenty people regularly filling the small room that was to be the theater. My Poe show moved to The Waverly Inn, in Greenwich Village, and near another of Poe’s New York City homes. The show ran as dinner theater for almost three years, until the restaurant was sold and the new owners converted the room into sports bar.

In the meantime, Poe had several bookings. One, in Scranton was seen by the management of the Scranton Cultural Center. The Center is a huge, magnificent Masonic theater. Its managers invited me to enter a contest they were holding to find a play on coal mining and a famed strike of 1902, for “The American Celebration of Labor 2000.” Scranton in the 19th century was a hub of coal, steel and railroad monopolies, and the home of the United Mine Workers of America which was led, at the turn-of-the century, by the charismatic ”boy” president, Johnny Mitchell.

With other invited writers, including some quite prominent, I submitted a proposal for the festival play. I dashed off a rough outline with a finale of figures from the history of labor abuse, beginning with the Triangle Shirt Manufacturing disaster (when the women workers burned to death because the door of their work loft was kept locked), to children in Southeast Asia making America’s most fashionable sneakers. I’d come to know a Dutch radio journalist, Anton Foek, who contacted me, interested in “Vriesland.” An advisor to the United Nations, he was just breaking this story of virtual child slave labor. My history-spanning “finale” won me the commission.

The show was produced and met standing ovations, including from the current president of the United Mine Workers.

When I tried for this commission, I knew nothing about coal mining though I live only a few miles north of vast, closed down mines. But research is my business, and there were many still living whose fathers died in the mines. One elderly man, as a boy went into the mine near his backyard and fed the mules that were still down there. It was believed that, once they had worked in the mines, then saw sun light, the mules would go crazy, so the animals had been abandoned down in the dark.

I talked with former “spraggers” who, at about age 12, slept with their mules, fed them and shared their chaws of tobacco with them. Boys, 5 or 6 years old, were hired for pennies to open and shut doors deep down in the tunnels. Any family that lived in a mine-owned house had to have a family member employed in the mines or they were evicted. Hence the jobs for 5-year-olds were worth more than their penny salaries. Writing “Johnny!” was fascinating, and chilling.

Yuh ain’t got a lunch. Here, have a bit o’ mine.

An’ don’t yuh go t’ sleep, little nipper.

Many was the nipper fell asleep

An’ met his Maker

When the train come rollin’ through…

Smell o’ coal lulls yer sense

Stay awake, keep defense,

‘Cause the mine’s breath’ll swallow yuh live.

Close yer eyes an’ yer dead,

Keep that in yer head.

Stay awake, little nipper, stay awake.

‘N’ when y’ hear the whistle blow

Up above yuh can go.

One chance less the mine has t’ claim yuh.

Yer day’s work is done,

Go back like we come.

Stay awake, little nipper, stay awake.

My next project was “The Treasure.” With a friend, I was visiting Transfiguration Monastery in Windsor, New York. As my friend haplessly chased her 4-year-old over the lawns, the prioress mentioned that they were looking for someone to write their foundress’s story for film. Of course I offered.

With months of interviews, with elderly Sister Placide lapsing into French every little while, I gleaned the story of how, as a novice nun in a secluded convent in the Pyrenees, she took part in concealing the Belgian National Treasure from the Nazis.

The Germans were under orders to find the treasure, and to use the convent as their rest and rehabilitation center. How Sister Placide and her companion nun in Los Angeles unwittingly became sort of renegades, causing havoc with the diocese and leading HBO to withdraw interest in “The Treasure,” is a story for comedy.

Perhaps, one day, Sister Placide’s story of bravery in outwitting the Nazis will be made into a film.

Although my father won an Oscar for the original story and screenplay of DeMille’s “The Greatest Show on Earth”, when he was no longer a staff writer for DeMille he went years without selling a script, until “El Cid” was sold to Samuel Bronston. From him I learned infinite patience.

These days, I live contentedly with my husband, Peter, in a house we’ve “improved” for over 40 years, beside our beautiful waterfall. I garden. I read. And we enjoy our dogs and cats.

We’ve had many animals over the years: sheep and horses, with a splendid Great Pyrenees named Thibaut to guard the sheep. We’ve had seven Papillons, a pair of German Shepherds, as well as chickens, peacocks, geese, ducks and goats.

At present, we have no more farm animals But Kiku and Kirin our Japanese Chins, Geoffrey our Yorkiepoo and our adored Chihuahua Jolie ( who is loudly snoring at the moment) are our delight. All but Geoffrey are rescues.

And there are five cats: old Buddy from a shelter, and Rainey who we found starving in the snow on our terrace three years ago. That spring she presented us with three kits. They’re a fascinating family; though her kits are grown up now, she still lovingly grooms them.

What can I say of my life? Since childhood, it’s been full of good surprises. When I was a child I thought the worst thing was a life of hard work that achieved recognition only in dying days or after death.

Wisely, knowing that a life in the arts was subject to frustration, I made a point to have my private, daily life happy, with a home and objects I found beautiful, that gave me joy, all shared with someone I loved and found boundlessly interesting. Peter has been that person for me. Although most of my work has encountered obstacles, I’ve loved doing the work, and feel I’ve done good things. To love and to be pleased with what one has done is, I think, the highest happiness.