Contemporary Artists Inc. was a fine art print publishing company located in New York City, 1971 -1977. Founder and director: Katherine Ashe (neé Ann Frank). Business director: Peter Davidson, (former Treasurer American Airlines). Advisor: Paul Cummings (founder of The Print Collectors’ Newsletter and The Drawing Society, advisor to the Whitney Museum for works of art on paper, author of the Dictionary of Contemporary American Artists).

Contemporary Artist’s policy was for each artist to participate in the print making process. It was a common practice for some artists’ watercolors or guaches to be sent to a printing plant where craftsmen would draw the color plates or the image would be transferred photographically.

Thirteen Artists for the Bicentennial Portfolio

The Bicentennial Portfolio consists of 13 prints, eight by artists with prominent careers circa 1975, five up and coming artists. The intention was to provide a view of American art at this point in the nation’s history. The project was thirteen editions, each with seventy-five signed and Arabic numeraled prints for commerce, to be sold by Contemporary Artists Inc. through major galleries nationwide; and twenty-five signed and Roman numeraled prints in a special boxed edition given to museums (MoMA, Art Institute of Chicago, etc.) The project was funded by Lawrence Corwin. Katherine Ashe (neé Ann Frank) chose the artists, contracted with them, supervised the artists and printers and, with the artists’ approval, asked the printers to “pull” every “state” of each print for what was planned to be a touring exhibit of fine art printing techniques.

Contemporary Artists Inc.’s policy was that each artist make the “plates” of his or her print. At the time it was a common practice for artists to give to his printer a watercolor or gouache of the work intended for the “original, signed, numbered print.” The printing firm employed copyists or used photo reproduction for the edition. Some artists (Pond and Anuszkiewicz) customarily made their own prints. Some habitually worked closely with their printers (Bolotowsky, Porter, Barnet) Others, although they had many limited edition, signed prints in commerce, had never been directly involved with print making (Beardon.) And for some, this edition was their first experience with print making (Remington, Meng.)

The collection donated to the Wyoming Seminary includes these “states”, the silk screen of the Clayton Pond print and four of the aluminum plates and a transparency from the Romare Beardon print.

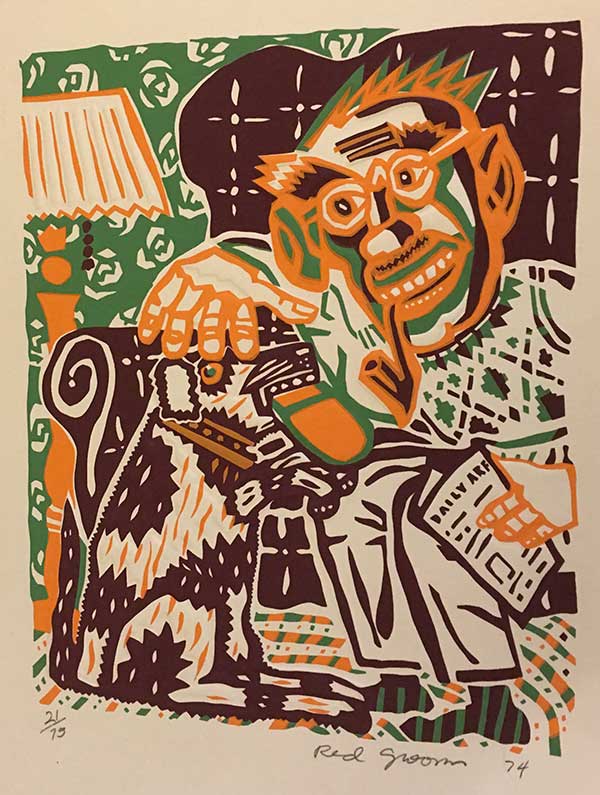

Richard Anuszkiewicz

Silk Screen “Red, White and Blue.” Cancelled with overprinting or a hole cut in the print. Pirating of limited edition prints was common in the mid-1970s. Anuszkiewicz made his own silk screen prints in his Englewood, N.J. home studio.

Darby Bannard

Silk Screen, no title. Printer: John Campione. It was Contemporary Artists’ aim to match artists with printers responsive to their style, work habits and personalities. Darby Bannard found John Campione so congenial that together they generated a series of monographs as Bannard experimented with the serigraph medium and the optical interrelationships of colors. The final result, final only because time and funding were running out, was not necessarily the most pleasing but the process of color experimentation pleased both artist and printer.

Will Barnet

Silk Screen girl with book: Barnet’s serigraphs were very popular. Usually of people, his images are two dimensional and in iconic poses. He employed his customary printer and the image was used again for a library promotion.

Romare Beardon

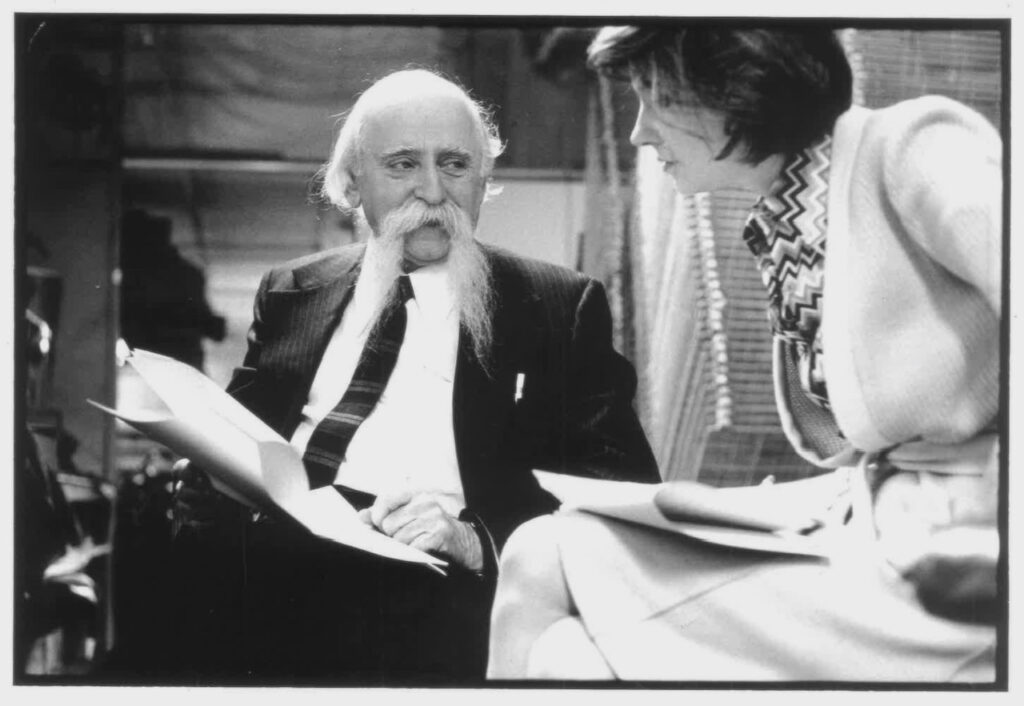

Lithograph on aluminum plates: “Sunday Morning”. Printer: Paul Narcowicz. When Ann met with Romare in his studio he presented her with a pile of small watercolors. She explained that CA Inc. wasn’t going to reproduce an already existing work, but that our policy was for the artist to make the plates himself so that the final print was indeed an original work. Romare chose a watercolor of a woman and baby, a black interpretation of a virgin and child as the basis for his print. Although he had many fine art prints in commerce, Romare himself had never actually worked on prints.

In his atelier near New York’s City Hall, Paul set Romare up on a stool by a high table with a transparent sheet in front of him on which to draw in ink the outline guide for the print plates. Next, Romare was presented with large gray sheets of aluminum, a jar of acid and sable brushes of various sizes. Each aluminum sheet would be used for one color only, with the ink drawing on the transparency as guide. There would be no photography, only what Romare drew.

The edition was printed and, in a rather dubious tone, Paul summoned Ann to see it. There was the image of Sunday Morning in all its colors, but with peculiar white squares each marked with an X. Romare was as distressed as Ann was. The X, he explained, was for the printer to fill in with a flat, solid color. The match of Romare with Paul was not a completely happy one. Narcowicz, a superb printer, was something of a perfectionist and Romare, in middle age and at the height of his career and life, was shy to ask him basic questions. The result was that all the plates had to be done over again with Romare filling in the X marked spots.

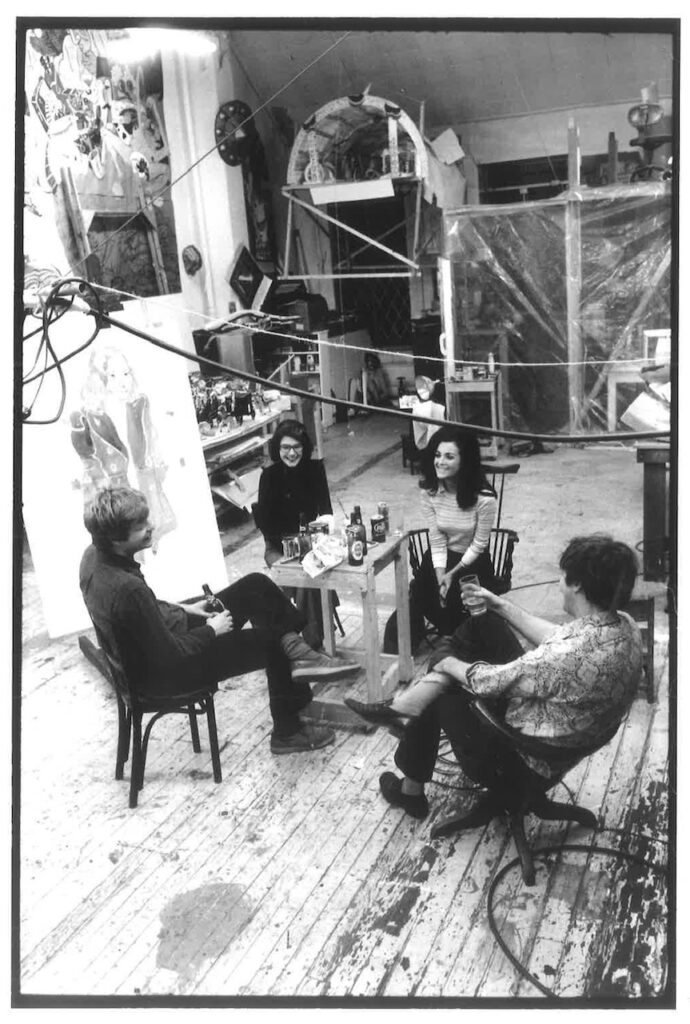

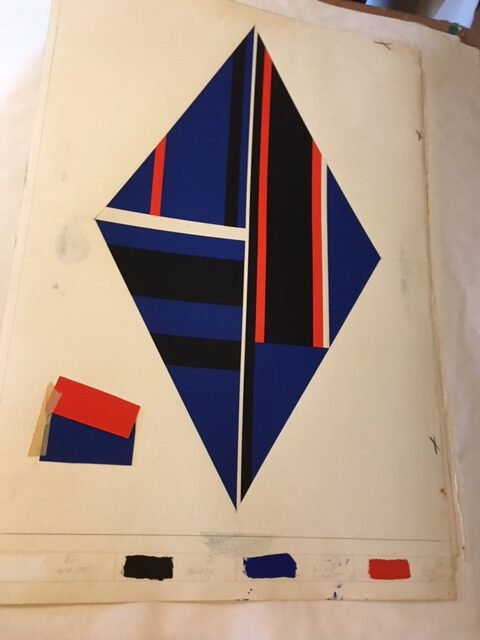

Ilya Bolotowsky

Silk Screen “Blue Diamond.” Printed by Michael Knigin at his Chiron Press on Fourth Avenue near Union Square. Ilya, with his wife, son Andrew, a flutist, and Andrew’s fiancée lived in a loft on Fourth Avenue near 10th street, and Ann Frank, who lived at 9th Street and Third Avenue, became lasting friends with them. A group of aristocratic Russian emigres often met at Ilya’s loft. Sitting at his round oak dining table with his collection of liquors forming a bottle-scape in the table’s center, they would reminisce about the Revolution; Ilya remembered bullets breaking the library windows and lodging in his father’s books. Or he would chuckle about his encounter with Zsa Zsa Gabor who was fascinated by his great, white, walrus-like moustache.

Janet Fish

Lithograph “Canned Peaches.” Burr Miller, printer. From fond memories of her grandmother, Janet loved cookery and canning. Burr used an enormous Miehle press with a row of little spigots, each of which could be tweeked to precisely control the flow of ink. Of course only one color was printed at each run and the huge press would be cleaned for the printing of the next color. Burr’s aluminum plates were bent into a circle around the press’s drum and Burr would climb up on the massive machine to adjust each spigot as the paper ran through the test printing of each color. Burr, as his name suggests, was born into a family of printers.

Alan Kessler

Aluminum Plate Lithograph “Geranium.” Burr Miller, printer. Alan’s work was just beginning to receive notice at the time this print was commissioned by CA Inc.

Alan and Wendy Meng were married and lived in a loft in SoHo “South of Houston”, the region of New York City between Canal Street and Houston, popular with artists because the buildings were chiefly old factories with large, open floor space and freight elevators suitable for the very large art works being made then. With a special AIR (artist in residence) legal designation by the city, these lofts could be renovated into living spaces by the artists themselves. Gradually SoHo lofts became fashionable and the artists often found their renovation work was more lucrative than art, with the result that many spent much of their time installing kitchens and bathrooms. From being very cheap artists’ housing, Soho became wildly expensive, with ultramodern boutiques and international stores and hotels.

“Geranium” was Alan’s first print. With Burr’s guidance he did a lot of experimenting, using a brush dipped in acid to “bite” the wax-covered plates for each color. Surprisingly, sable brushes hold up rather well in this technique.

Wend Meng

Stone Lithgraph “Fish.” Paul Narcowicz. A massive, fine grained gray stone about five inches thick was mounted on Wendy’s similarly massive easel; Wendy sat, dabbing with her acid-dipped brush directly on the stone which was extremely delicate of surface. It was a pains-taking procedure as there could be no errors. Just as she was finished at last, Wendy sneezed. The tiny droplets “bit” the stone, creating the “bubbles” which, in CA Inc.’s official opinion, enhance the surface. The director of the print department of the Art Institute of Chicago, receiving the boxed gift edition, declared the Meng print especially fine.

Wendy had never done a print before. She was, in fact, only beginning her career as an artist. When Ann went to commission the Kessler print, Wendy was just finishing a huge painting of an angel fish with a magenta coral background. Ann at once bought the painting and commissioned the print. Wendy’s next paintings were sold as soon as finished, bought for a Rockefeller collection, Lever House, etc.

Clayton Pond

Silk Screen “The Working End of My Gas Space Heater.” Printer: Clayton Pond. Clayton’s whimsical imagery is particularly apt for serigraphic solid colors and his skill in building his colors is unsurpassed. The single screen used for all the colors is included with all the “states” in the Bicentennial Portfolio Technical Study Collection.

Fairfield Porter

Lithograph untitled: sun over sea: Printer: Resam Press/ J. Samson. This lovely sunset or sunrise image was Porter’s last work. The day after signing and numbering the edition he died while walking his dog. He was both a lovely, gentlemanly person and an artist who could capture an ineffable, spiritual quality in vison.

Joseph Raphael

Lithograph “Water Liles.” Printer; Tamarind. Joseph had just returned from Hawaii with a batch of photographs of Mount Kilauea’s eruptions as studies for paintings or prints. Ann had high hopes of commissioning a volcano but Joseph preferred the more subtle imagery of Hawaiian waterlilies. The printer has given the artist full opportunity to experiment with many plates. Tamarind, in Taos, New Mexico, was considered the best fine art printing atelier in the US and artists were happy to spend weeks in Taos to work with their craftsmen. Picasso’s wife, Francoise Gillot was just completing a series of prints there as Joseph began. (Mme. Gillot, leaving Tamarind at the end of her work day with a big, soft leather bag full of weighty metal containers of inks, was mugged. She struck the mugger with the heavy, lumpy bag, injuring him and facing charges of assault. Tamarind saw to it the charges were dropped.)

Deborah Remington

Serigraph untitled. Printer: The New York Institute of Technology. The technique of gradually blending one color into another was fairly new in 1975 and NYIT was in the forefront of its development. This was Remington’s first print, and the image, suggesting a furnace or womb, is typical of her paintings. Deborah Remington is a descendant of Frederic Remington in a family full of artists, most lesser known, but her cousin Barbara Remington’s most readily recognized works are the original book covers for the first American edition of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings — which set the imagery for the films. The Remington family’s visual imagination could hardly be more varied.

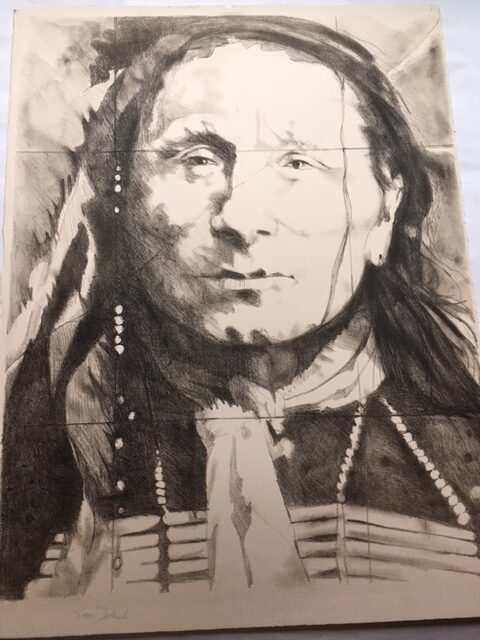

Barbara Sandler

Lithograph Indian spirit dancer. Printer: Burr Miller. Barbara specialized in large drawings and paintings adapted from old photographs, often with a grid such as copyists used, lightly superimposed on the image. Barbara had done a series of faces of American Indians but was beginning her series of people with extensive tattoos – such tatoos were a rarity in 1975. Ann chose this tender Indian image for the bicentennial. Restrikes of this image, being offered on line for $850 (7/21/2019), are accompanied by an admittance that they were printed in 1985. They are being offered for sale as originals although the offering clearly states the portfolio of which the prints are a part was printed in 1975-6. CA Inc. made great efforts to avoid piracies, but in this case the plate was retained by the printer and what may have happened to it subsequently is unknown.

Footnote: The building that housed Barbara’s studio, on Madison Square, was rich in the aromas of oil paints, turpentine, linseed oil and damar varnish. John Campione’s printing workshop similarly was filled with the perfumes of chemicals used in art processes. On a memorable occasion when Darby was working on his edition, first a gentleman in an overcoat arrived with an old brass goose-necked lamp, and left the lamp. Then another gentleman came equally mysteriously and left a briefcase. The objects were to be picked up by the woman who entranced all three of these men – Barbara Johnson, the widow of Philip Johnson of Princeton, an heir of the Johnson and Johnson pharmaceutical fortune. At length Barbara arrived, shouting up through the volatile fumes of the stairwell, “My skirt is on fire!” And, indeed, her heavy tweed skirt was smoking furiously, ignited by an electrical short under the dashboard of her car. Fortunately the building didn’t explode. Barbara left, safely quenched, with the gooseneck lamp and briefcase in hand.